This article originally appeared in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. This version has been abridged.

Threads Of Identity

For some who dress in dramatically different ways, what’s outside expresses what’s within

By Catherine Fitzpatrick

of the Journal Sentinel staff

February 14, 1999

He has been chased by ruffians wielding knives and stones. Been screamed at, jeered at, questioned brazenly by strangers.

Once, in autumn, he entered a public elevator alongside two teenage girls. They eyed him head to toe, giggly with curiosity. Then one of the girls piped up: “So, who are you supposed to be?”

He replied sharply, “What?”

As a rabbi, he was more bewildered than angry.

Then he remembered. It was Halloween.

Such are the pinpricks that can be suffered by those who dress in a fashion so dramatically different from the rest of us that their clothing might be mistaken for costume.

Yet throughout the Milwaukee area, a number of citizens spanning a broad spectrum of backgrounds and beliefs eschew current style trends. Rather, they clothe themselves every day in the traditional attire of their native country or their ancestral homeland, or in a manner of dressing prescribed by their religion.

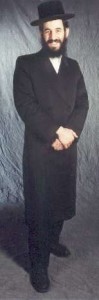

Here’s a closer look at an area resident for whom substance determines style.

Like all teens, Benzion Twerski yearned for new clothes. Like many parents, his father made him earn them.

It took the boy years.

At 13, youths in the branches of Hasidic Jewish life with which the Twerskis are associated receive a four-piece ensemble. It will be their wardrobe for life.

“When I was 10 or 11, I told my father I wanted to dress, at least on Shabbos (the Sabbath), in a more Hasidic garb,” said Benzion, now an adult.

His father, Rabbi Michel Twerski, said he would buy young Benzion a Shabbos bekeshe (long tailored coat). But first, the boy was to learn a tractate of the Talmud, the collection of writings constituting Jewish civil and religious law. Such a project normally takes a year of study.

Working with a special tutor every day during the lunch hour, Benzion concluded the tractate in 7 or 8 months, and received his bekeshe. Repeating this arduous process three times earned him a Shabbos hat, a weekday coat and a weekday hat.

Benzion Twerski is a Hasidic Jew, the third generation of rabbis to guide Congregation Beth Jehudah on Milwaukee’s west side.

Hasidic Jews are Orthodox Jews, Benzion explained. Chassidism differs from other types of orthodoxy in its flavor, not in any fundamental capacity, he said:

“It is much more of an attitudinal, atmospheric type of movement, easily identifiable by dress most of the time.”

Of all the aspects of Hasidic life, the dress code is the most widely embraced because it is the easiest, Twerski said. “The others are far more soul-searching and involve much deeper commitments.”

The clothing, he explained, is intended to drive home to the person that there is something expected of you:

“The hope is that the garb will influence (the wearer) and bring about the things that Hasidic Jews hold dear: joy, intensity in service, kindness to others, love of the Torah.”

By Benzion’s count, five or six Orthodox Jewish men in Milwaukee dress in traditional Hasidic manner.

During the week, the wardrobe consists of a wool bekeshe (a suit with long tailored jacket) in black, dark gray or dark blue; a white shirt; a brimmed felt hat. Formal Shabbos attire differs somewhat, in that the bekeshe is black satin or silk, and the hat (called a streimel) is circular and made of fur. As an Orthodox Jewish man, he also wears, under his jacket, a rectangular prayer shawl with tassels (tzitzis) at each corner.

Orthodox Jewish women take care to dress modestly, but have no proscribed garments. Married Orthodox women, however, cover their natural hair at all times — even in the home — with either a scarf or fashionable hairpiece.

“One of the concepts of Jewish law is that the beauty of the hair is something that should be preserved for the husband’s sake only, something to be shared between husband and wife,” Benzion explained.

Benzion and his wife, Chanie, have five children. Their sons, who wear long side curls, have been teased. “My kids will come home sometimes very upset,” Benzion said. “It’s cruel.”

And yet the third generation of Milwaukee Twerskis expects the fourth generation to adhere to the Hasidic rules of dress, rules that dictate full beards, long side curls, yarmulkes, bekeshes, streimels, scarves and hair pieces.

“Garb is an expectation that’s almost inbred, it’s unquestioned,” Benzion said. “What would I do (if they chose not to follow the rules of dress)? I wouldn’t do anything. It would be their choice, but it doesn’t even occur to me to be an item in question. The track record speaks with power: We’ve been dressing this way for about 11 generations.”

The Twerski family lives in a stone home on Milwaukee’s west side. There, an elegant lace tablecloth, a collection of candelabra, and kiddush cups for wine-blessing give the dining room an Old World ambience. Seated at the table, Benzion could be mistaken for a man of the 18th century, until he checks his phone messages on a palm-size pager, and quiets his toddler with bits of kiddie breakfast cereal.

Benzion Twerski’s clothes are meant to convey this message:

I am in your world . . . but not entirely of your world.